Definitions of “Flavor” – Implications on Taste Masking

What is Flavor?

We can trace the origins of many dosage forms and pharmaceutical technologies back to the food industry – and today we consider it a rich source for approaches, tools and methods that pharmaceutical scientists can adapt to develop palatable drug products.

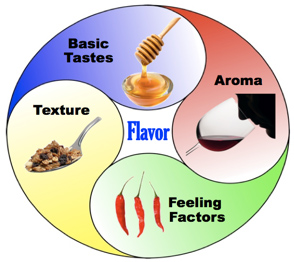

How do we define flavor? This might seem like a simple question, but it gets confusing outside of the food industry. To a food or sensory scientist, the term “flavor” refers to the combination of taste, aroma, mouthfeel and texture. Since we will talk extensively about these terms in this blog, we’d like to take a moment to define them.

Taste

“Taste” refers to those sensations perceived through the stimulation of the receptor cells located in the taste buds on the epithelium of the tongue and oral cavity. The oral cavity perceives five distinct tastes: sweet, sour, salty, bitter and umami (savory). We refer to these as the “basic tastes.”

The receptor pathways differ across the basic tastes. Sour and salty are ion channel receptors, detecting H+ and Na+ ions respectively. Sweet, bitter and umami are mediated by G-protein complexes, which initiate signal transduction cascades upon detection of target molecules, leading to taste perception. Sweet, bitter and umami also share a complexity in the number of identified receptor types for each taste.

Aroma

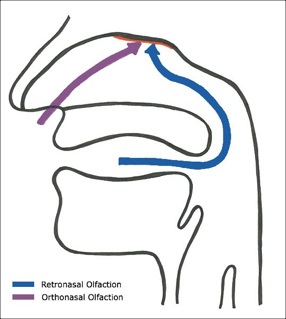

Odors (aromas) are volatile chemical compounds perceived via the sense of smell (olfaction) through stimulation of receptor cells in the olfactory epithelium located in the upper reaches of the nasal cavity. These volatile aromatics reach the olfactory epithelium two ways: via the nose during normal breathing (orthonasal olfaction), or via the nasopharangeal passage during mastication when air is exhaled through the natural action of swallowing (retronasal olfaction).

Source: Wikimedia Commons

Most scents in nature are mixtures of volatile chemical compounds, very rarely are these perceived individually. For example, the scent of a fresh piece of fruit could be comprised of several hundred separate aroma chemicals – each a different concentration (ppm to ppt). Furthermore, the aroma identified by the brain is the complex interaction of this mixture, ratio, and their absolute concentrations, yielding more than a trillion possible smell combinations.

Mouthfeel

Mouthfeel refers to sensations (feeling factors) that arise when chemical compounds directly stimulate free nerve endings in the trigeminal (Vth cranial) nerve. We refer to this as chemesthesis.

Examples of feeling factors include cooling (produced by compounds such as menthol or mint), numbing (produced by compounds such as clove oil or parabens) and bite/burn (produced by compounds such as pepper or ethanol).

These are part of the general somatic sensory system, a subset of the pain and temperature-sensing nerves found throughout the body. Many APIs and excipients, such as solvents, emulsifiers, and preservatives, are known to produce this trigeminal irritation.

Texture

Textures are a product’s tactile characteristics perceived in the oral cavity. These include those surface attributes measured initially, as well as when a product is deformed through mastication (chewed, swished, rolled, agitated, or swallowed).

Notable textural attributes for oral liquid drug products include viscosity, smoothness, and mouthcoating.

For oral solid dosage forms, including chewable tablets, soft chews, and orally dissolvable films and tablets, important texture attributes may include roughness, hardness, fracturability and cohesiveness, depending on the specific form.

In summary, the term flavor refers to the overall perception of taste, aroma, mouthfeel and texture.

As we will discuss in future posts, each of these is important in developing palatable dug products, whether for children or adults.

Taste Masking Challenge? Senopsys Can Help!

Are you faced with the need to develop a palatable drug product to support clinical trials or commercial development? Our scientists are expert in both taste assessment and taste masking.

We use our experienced GCP-compliant taste panels and analytic tools to quantify the taste masking challenge and guide formulation development. And we apply a structured, sensory-directed development approach pioneered in the food industry to create palatable, taste-masked drug formulations for liquids, powders and solids.

Very insightful, do you find that the biggest challenge for most APIs is the bitter taste, or one of the other elements of flavor?

By far the most consistent negative attribute is Bitterness. This not surprising, as humans evolved a heightened perception for poisons, and at most concentrations (doses) drugs have negative health consequences. That said, while many/most drugs are bitter, we encounter additional challenges from offending odors or negative mouthfeels (e.g. burning), in roughly half of the compounds we evaluate.